Money is a sufficient incentive for many things. More generally, gaining any type of abstract currency that lets you buy any good is a sufficient incentive. In today’s academia there is an abstract currency that lets you buy several things such as a PhD degree (moderately expensive) or a professorship position (very expensive). This currency is called a research paper (paper in short) and the market is called the academic job market.

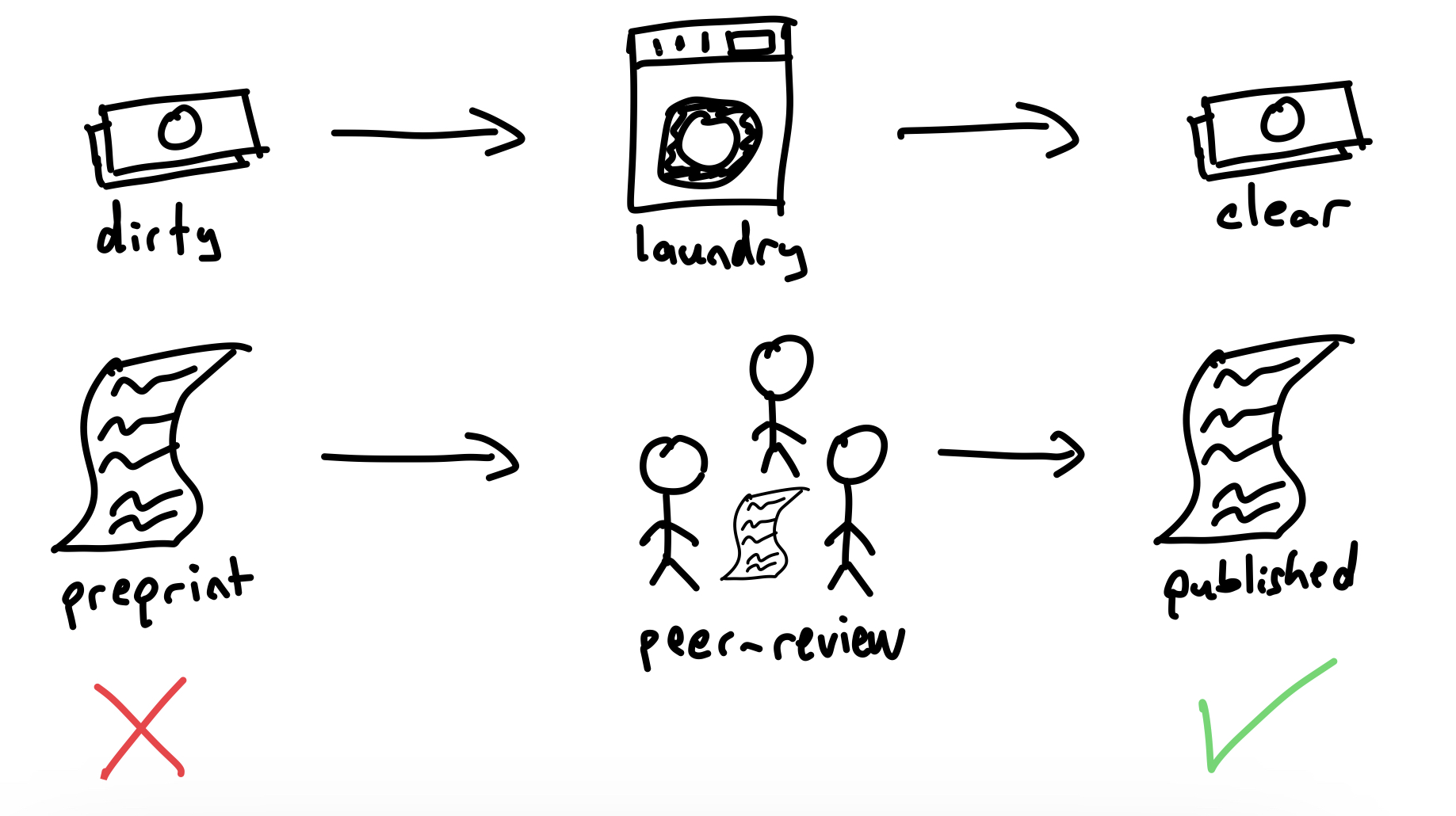

Although it is a tedious process, we can actually print a lot of this kind of currency. Like all other currencies there is a regulation mechanism which decides whether a given paper is fake or not. However, there is not a central bank that prints a valid kind of this currency. Hence all the money is technically printed in the house. The validity depends on whether some selected set of other printers (called reviewers) agree on the validity of the paper or not. If they do, it is a valid paper that you can spend. Otherwise either you throw it away or you try to make it look like an original paper to further convince the reviewers. It is actually very similar to money laundering. In essence, all printed papers are assumed to be dirty by default and they are being laundered by a set of reviewers so that they become valid. Note that although I use the term laundering this is not an illegal process since this is the only and the default way of obtaining this currency. This initially printed dirty state is commonly referred as a preprint and the laundered version as published. This laundered currency is maybe the only accepted currency in the academic market and it is so important that people have coined the term publish or perish.

Too Many Papers

One of the underrated problems with the current publishing system is that there are too many papers. As we have already said, everyone can print papers, but there is a limited number of reviewers who can check their validity. Some venues even force every submitter to also act as a reviewer for the same venue in order to facilitate the reviewing process. By the way, have I told you that the reviewers are working for free? Well technically not. They are incentivized by an imaginary preaching: “you are a noble being and you are participating in the path of telling the truth and falsehood apart”. This statement lives rent free in many reviewer’s minds but I guess it is just not enough (as you might also have guessed).

With the large amount of papers and many other reasons that are irrelevant to this article, the reviewing system is not functioning properly. With reviewers being overwhelmed by the task at hand and papers with many errors getting accepted to well respected venues. It is not even clear whether it makes sense to have a system at this point because it is unclear how many of the papers actually end up being read. My favorite example is again NeurIPS 2021, where 9122 papers were submitted and around 2000 of them were accepted [1] (seriously, who reads this stuff?). Some papers are arbitrarily long and it is not uncommon to see a paper in a well respected journal which looks completely obfuscated even to a well versed reader. This is natural because there is no way to see on which basis the paper was accepted. This last sentence is about the issue of reviews being private and there has been a lot of good efforts to resolve this lately such as review commons.

One question that motivated me to write this article was “Can we encourage people to focus less on the number of published papers and focus more on reviewing both other’s and one’s own work?”. This leads us to the second problem of incentivizing peer review.

Incentivizing Peer Review

There have been different approaches for incentivizing peer review, both with monetary and non-monetary incentives [2, 3, 4, 5] . Most non-monetary incentives I have seen so far [2] are quite weak. These include very funny incentives such as giving an annual journal subscription for free to the reviewers of that journal (I mean, really?). More logical ones [3] include giving more public recognition to the reviewers. This seems like a better approach because this public recognition can be used to gain academic positions in the future, however, the hiring committees should adapt their views to consider this additional public recognition in addition to the applicant’s published papers (they need to start accepting an additional currency, if you like the analogy).

For the monetary case, outright paying for reviews just don’t work, this even results in a negative incentive where the reviewers view the act of a paid review less noble and reject the request. This is not a logical behaviour but academics tend to care less about money or at least they tend to act like they do not.

What I would like to claim is, there is one and only one incentive to capture a lot of scientists to do better reviews in a sustainable way. Can you guess? Yes, more papers!

If doing X yields more papers, scientists would willingly do more of X.

For more senior scientists, “papers” can be replaced by “grants”. I am aware that this statement portrays scientists as if they would do anything to publish more papers but for the specific case of reviews, I think many people would do more reviews or do the same amount of reviews more willingly, if they were able to publish more papers in exchange. This is not backed by any statistical argument, just by a handful of personal observations. So let’s assume that we will give papers in exchange for reviews and expect to incentivize peer review in this way. As you might have guessed, we still have a serious problem. How do we give papers to people?

We previously said that anyone can print a paper and try to make it published. However, we still can not print them out of thin air (the process is not easy). Moreover, we can not give an arbitrary published paper to someone else (the currency is not transferable). What we can do instead is to artificially limit the amount of papers one can publish, and enable them to publish more in exchange for reviews. So instead of considering the papers as a currency, we consider the act of publishing as a currency (i.e. with this currency, you can purchase a right to publish). We simply reward this currency to the reviewers and see what happens.

The Review or Perish Approach

The rest of the article explains the high level idea in a more structured way to describe the macro mechanics of the system more explicitly.

Setup

We assume that we have a set of uniquely identified users (this is a strong assumption that requires further discussion). We define the following setup for the publishing system.

- Each user receives a fixed number of publishing tokens when they enroll. Let’s call this $n$.

Preprint Pool

- Any user can upload as many papers to the preprint pool as they want. This action has nothing to do with how many publishing tokens one currently holds.

Important Note: I would like to stress that anyone at any point can upload as many preprints as they want. It wouldn’t make sense put a limit on what people can actually upload.

Published Pool

- There is a pool of published papers. Papers may only end up in this pool as a result of a well defined promotion mechanism.

The promotion mechanism

- This mechanism moves papers in the preprint pool to the published pool. In our previous analogy, this is the part where the laundering (reviewing) happens. When a paper is moved from the preprint pool to the published pool, a publishing token is removed from one of the authors. The token is removed from the author with the highest number of tokens (at random if there is a draw). If the paper is about to move from a preprint pool to the published pool, but none of the authors have any tokens, it simply stays in the preprint pool until one of them has any.

- Q: But wait, if it is not possible to publish after you are down to zero tokens. Can I only ever publish $n$ papers?

- A: No.

- Q: How do I gain more publishing tokens?

- A: Simple, you have to participate back in the promotion mechanism.

Note: Formalizing the ideal promotion mechanism is a non-trivial task and something that currently keeps me busy in my free time. The purpose of this article is to give a high level idea of its functionality. Feel free to contact me if you would like to brainstorm about the formalization.

Sharing publishing tokens

Although the tokens are not transferable, they can technically be shared by co-authorship since only one token is taken from the whole author pool in order to publish. This is intentional and the goal is to create an analog of grant writing for senior academics. For instance, a senior professor can invest some time in the promotion mechanism to gain some tokens more than one needs. In the future, it will help for their students to publish results when the students run out of their publishing tokens. Obviously, this would immediately create a blackmarket for co-authorship but this is just a first order approximation to the system and several mechanics can be introduced to handle this. There is already a natural negative incentive in play for fake co-authorships because people tend to desire less co-authors in a single paper. But still, this negative incentive will hardly be enough.

People can also team up and split the work of reviewing and paper writing where one constantly reviews papers and the other constantly writes so that both maintain enough tokens all the time. I don’t know if this would create a problem but at a first glance, a person with a bunch of literature knowledge and a person with a lot of writing experience would make a nice research duo. In the end, it is not about making everyone reading papers but at least some properly do. Paper reviewing could even be an independent job just like security auditors or test engineers.

Peer Review as a Promotion Mechanism

In our world, the promotion mechanism would obviously be the peer-review process. I tried to abstract it away in a different name because it is not clear whether we actually need peer-review (at least in its current form). Anyways, in order to work as a promotion mechanism, peer-review needs to have the following properties:

- Paper Submissions are permanent: This is a no-brainer. It doesn’t make sense to resubmit a research paper. One can only announce it as withdrawn. Otherwise, it is clear that the authors will take another chance of resubmitting to another venue. Might as well keep it submitted in a single pipeline.

- Reviews are public: Once we resubmit a paper, all the previous review information is lost. Hence, it is not possible to check whether the previous reviews were taken into account or not. This is the very reason peer-review is viewed as a stochastic process since the submissions are indistingusihable in front of different sets of reviewers. Criteria 1 solves the resubmission problem, making reviews public enables people to check the sanity of the reviews and lets other reviewers take the old reviews into account.

- Anyone can review: You are gonna be mad at this one but hear me out. First of all the current system does not even allow us to check whether the reviews are good or not. Why do we outright believe that the selected set of reviewers are not worse than any other people? Who is watching the watchmen in the current case? The counter argument would be true if we were to say we are going to pick 3 random people in the world to review your paper and that’s it. There can actually be a lot more than 3 reviews (as many as people want) and if there are enough reviews, it is likely to contain decent reviews. It is tempting to say people will hire trolls and shill their own work. I don’t agree, because these are not very hard to identify, especially when they are public.

- Poor reviews doesn’t count: We don’t just want more reviews, we want ones with enough efforts put in. So participating in the promotion mechanism would mean writing good reviews (as in putting enough effort). In my opinion this is the hardest property to achieve because it is not easy to determine what constitutes a good review. But again, when everything is public, it is considerably easier to measure one’s effort.

What we obtain at the end is a system that encourages writing more/better reviews and especially, taking the time to read the papers and write the reviews since you literally wouldn’t be able to publish something without doing it anyways. This also naturally reduces the amount of “published papers” (not preprints) since reading a paper takes a considerable amount of time so reviewing is not a very fast process.

Another approach I have seen before [6] attempts to penalize people who submit late reviews or completely reject review requests by making their papers stay more in the editorial process, essentially delaying the publication. Although it is in the same spirit of “incentivizing via papers” it is incentivizing doing reviews in time and does not really contribute to the problem of too many papers.

Who Runs the System?

Until now, I haven’t talked about the actual entity that is running the system. I think there are many alternatives such as being centralized/decentralized. Being subject oriented, field oriented etc. The only thing I know is that it is not supposed to be run by journals. Never!

Although this system can be equipped by different journals and conferences, I don’t think journals have any utility in today’s world and given enough participants, the system can work on its own. Different fields may instantiate different instances of the system in order to have separate pools but this should not exceed more than one in a field. Otherwise, it would boil down to having journals.

Journals charge around 3000$ for putting blue ticks on papers.

— Abdullah Talayhan (@talayhan_a) November 22, 2022

Most people would like to argue that journals are there so that we know what to read from a bunch of papers. This is outright false. The Internet solved the “finding something relevant and noteworthy from a pile of irrelevant and unnecessary items” problem long ago. Scientists should immediately stop acting like this problem exists.

Conclusion

This was a thought experiment invoked by the idea of what would happen if we literally take papers as a currency for the academic job market and although it is not the most noble way of looking at them, could we leverage this concept to fix some of the problems in the current system. The first problem being the amount of papers being published and the second one being the lack of incentives for reviewing the papers (they are heavily dependent problems). The thought experiment resulted in the approach that I call as Review or Perish which artificially limits the amount of papers one can publish without participating in the reviewing process. I am not claiming that it is the ideal system for publishing, but I don’t see compelling arguments for the current publishing system we have anyways so why not think about alternatives. Hope you enjoyed it.

Disclaimers

-

This article takes a completely materialistic look at research papers and it is not the perspective that I actually endorse. But I think it fits well to how many communities look at research papers and how peer review would work from this perspective.

-

This article does not aim to undermine the people who spend time reviewing papers. It is a critique of the reviewing process.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

[1] An overview of NeurIPS 2021’s publications - (https://www.vinai.io/an-overview-of-neurips-2021s-publications/)

[2] Are non-monetary rewards effective in attracting peer reviewers? A natural experiment - Monica Aniela Zaharie & Marco Seeber (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11192-018-2912-6)

[3] Reviewing is its own reward, but should it be? Incentivizing peer review - Lauren Collier-Spruel (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/industrial-and-organizational-psychology/article/reviewing-is-its-own-reward-but-should-it-be-incentivizing-peer-review/8CB55199BA026C3571C9419C820FA361)

[4] Supporting robust, rigorous, and reliable reviewing as the cornerstone of our profession: Introducing a competency framework for peer review - Köhler et. al. (https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2020-08361-001)

[5] Does incentive provision increase the quality of peer review? An experimental study - Flaminio Squazzoni, Giangiacomo Bravo, Károly Takács (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733312001230)

[6] An Incentive Solution to the Peer Review Problem - Marc Hauser, Ernst Fehr - (https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.0050107&type=printable)